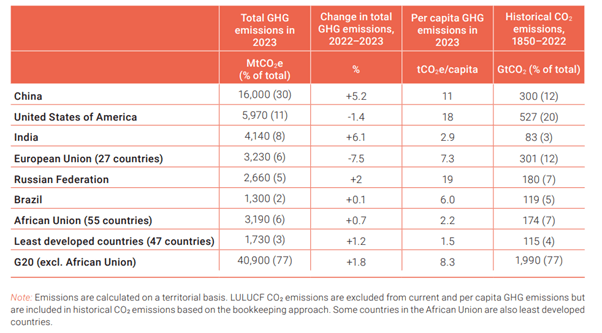

Analysis of Emissions Gap Report 2024

Figure 1. Source – Emissions Gap Report’24

The Emissions Gap Report 2024; No more hot air please!

In advance of COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, the UNEP’s Emissions Gap Report 2024 underscores the challenge and opportunity facing global climate action. While the need for accelerated mitigation is urgent, there are also vast, untapped opportunities to achieve developmental and environmental progress together.

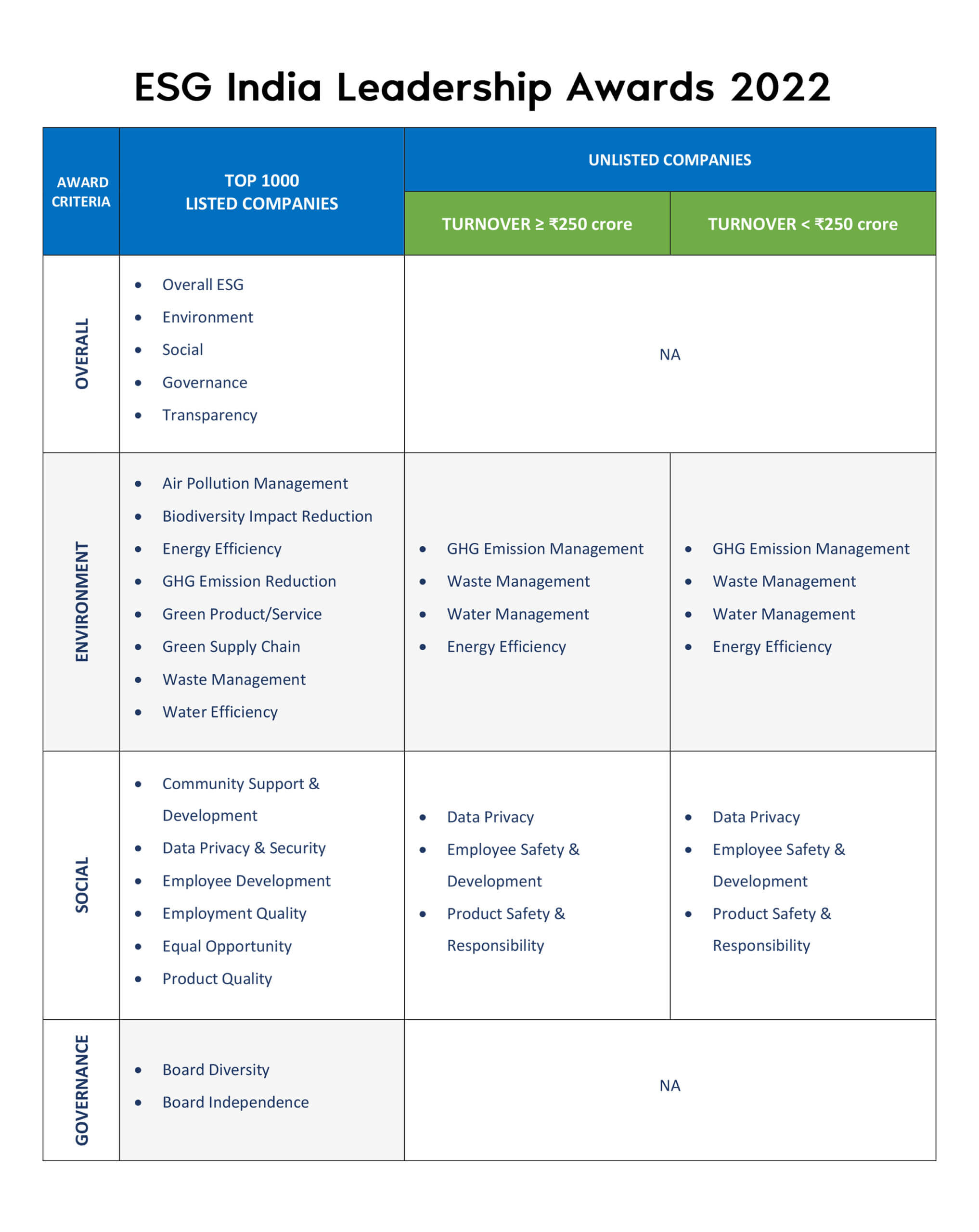

Table 1. Source – Emissions Gap Report’24

Here are some of the key findings from the 2024 Emissions Gap Report:

- The report indicates that if the status-quo remains, global temperatures are expected to rise by 3.1° C above preindustrial levels.

- The report estimates that to stay below 2°C, the remaining carbon budget is about 900 GtCO₂(GtCO2 means one billion tonnes of carbon dioxide). For a 1.5°C limit, only 200 GtCO₂ Current annual global emissions are roughly 40 GtCO₂, indicating that if emissions continue at this rate, the 1.5°C budget could be exhausted within 5 years.

- Delays in meeting targets have increased warming projections by around 0.01–0.02°C due to an additional 20–35 Gt of CO₂ added over this period. The emissions gap for 2030 is estimated between 15–25 GtCO₂ under current policies, exacerbating the path to meeting temperature targets.

- Solar and wind are highlighted as cost-competitive options, representing 27% and 38% of potential mitigation contributions by 2030 and 2035, respectively. For renewables, the report estimates that an annual increase of around US$500 billion is necessary to scale these resources sufficiently by 2030.

- Achieving a 1.5°C pathway will require approximately US$0.9–2.1 trillion in annual investments until 2050, mainly for emerging and developing economies. This represents a sixfold increase from current levels.

- Developed countries have pledged US$100 billion annually but have fallen short, with only US$83 billion mobilized as of the latest assessments. To reach the 1.5°C target, significant scaling of this finance commitment is crucial.

- Full implementation could lower projected warming to around 1.9°C by 2100, representing the closest alignment with the Paris Agreement target. However, without significant increases in ambition, the goal of 1.5°C remains challenging and virtually impossible.

ESG Risk.ai Analysis:

Historically, global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have long reflected a deep climatic and economic divide between the Global North and the Global South. The Industrial Revolution—starting in England and spreading across Europe and its colonies—fuelled large-scale use of coal, gas, and other natural resources, contributing massively to GHG emissions. Colonies such as India were leveraged for cheap resources and labour, a legacy that still shapes emissions disparities today. Many former colonies, only recently independent, continue to bear environmental and economic costs from this historical exploitation.

This divide persists, with high-income nations having historically contributed the most to GHG emissions. According to the above figure, India and China are now among the largest emitters, yet the context here is key. Per capita emissions in developing nations, including India, are far lower than those of the U.S. or other developed countries. Per capita emissions from developed countries remain nearly three times the global average.

While developed countries like the U.S. and EU have achieved modest year-on-year GHG reductions (1.4% and 7.5%, respectively), the six largest emitters still produce 63% of global GHG emissions, with the G20 accounting for 77% of total emissions. Least developed countries, by contrast, are responsible for just 3% of global emissions, underscoring the disparity in both contribution and impact.

Despite progress, challenges remain. While 90% of Paris Agreement parties have updated their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), most significant improvements were achieved in 2021 before COP26. Subsequent calls to strengthen 2030 targets saw limited response, with only one country committing to more ambitious targets since COP28.

As of mid-2024, 101 parties, representing 107 countries and covering roughly 82% of global emissions, have set net-zero pledges. Yet, these commitments vary in form: some are codified into law (28 parties), some integrated into policy documents like NDCs (56 parties), and others issued as governmental announcements (17 parties). The uneven nature of these commitments stresses the urgent need for unified action.